Photo by Andrea Piacquadio: https://www.pexels.com/photo/woman-in-yellow-jacket-holding-books-3762800/

In Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University, Kathleen Fitzpatrick acknowledges the American public’s negative perception of higher education and how many people believe that…

“We waste taxpayer resources by developing, disseminating, and filling our students’ heads with useless knowledge that will not lead to a productive career path, and—this part is true, but for reasons that the university alone cannot control—we leave them in massive debt in the process” (Kathleen Fitzpatrick, pp. 15–16).

Fitzpatrick labels this attitude as a misconception, but there is more truth in it than we in the academic community might be comfortable acknowledging. I agree with Fitzpatrick that the knowledge provided by universities is useful and plays a critical role in promoting healthy societies beyond career preparation, but higher education does have an ethical obligation to the future financial security of its students. Universities have taken for granted that those with a college degree will automatically find jobs after graduation, and universities need to actually listen to what the public is saying if they are going to survive.

In this paper, I quibble with Fitzpatrick’s assertion that higher education should primarily be seen as a social benefit rather than a personal one (22). Instead, I argue that universities should prioritize what our students say they need, career preparation, and push social ideals as essential but subsequent goals. By ensuring that our students can meet their financial needs in the long term, students will have more freedom as adults to contribute ethically to their communities and thus increase the overall social good. In this paper, I also explore how the humanities can respond to this reevaluation of the university’s purpose.

Why Prioritizing Careers Is Humane

Whenever scholars argue in favor of university education being a social good, they almost always list career preparation as a secondary goal. For example, Braskamp et al. assert that a college’s “critical mission should be to prepare students to become ethically responsible and active contributors to society, as well as critical thinkers and skilled professionals.” I believe those priorities should be flipped. Instead, the critical mission of universities should be first to prepare students as skilled professionals and critical thinkers. Subsequently, they should prepare students to contribute to society. Ethics should act as a guiding force and be interwoven throughout both roles.

This approach balks at education’s historical role as a social good. Yet, universities cannot hope to realize this goal of a more ethical and responsible society if individuals cannot meet their needs due to job insecurity. According to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, there are five basic needs that are hierarchical in nature, and the first must be met before the second, and so on. These needs are 1) physiological, 2) safety, 3) love, 4) esteem, and 5) self-actualization (Maslow 394). Employment falls into the safety category because employment protects people from the fear of not being able to meet their basic needs, like food, shelter, and water, which appear lower on Maslow’s hierarchy under physiological needs. Universities tend to focus on encouraging the ethical development of their students, which would fall under the self-actualization level of Maslow’s hierarchy, which is the highest level.

As a side note, Maslow never depicted his hierarchy as the pyramid that we so often see in popular psychology because he was concerned that people would misinterpret it as though lower needs had to be fulfilled one hundred percent before higher needs could be addressed instead of understanding that lower needs only had to be partially fulfilled before higher ones could be explored and that they were recursive (Kaufman).

While the fulfillment of needs is very nuanced, I think the general principle still applies that if a lower need is not met, it will be very difficult for a higher need to be realized. While universities do not strive to fulfill physiological, love, or esteem needs, although they can play a role there, they do directly affect safety and self-actualization needs. In previous generations, a college degree did all but guarantee a job, thus satisfying safety needs and allowing students the freedom to explore self-actualization. However, that assumption no longer holds true.

Society has changed so that a university education no longer guarantees that the lower tiers of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs are automatically met, and the American public has noticed this trend. If we follow Fitzpatrick’s advice to emphasize “listening over speaking,” there is a lot that we can learn from our critics (Fitzpatrick 4). Abha Bhattarai, an economics correspondent for The Washington Post, wrote about how it is currently more difficult to find a job with a college degree than without one in her article “New College Grads Are More Likely to Be Unemployed in Today’s Job Market.” She states:

Despite a surprisingly robust job market,recent college graduates have been having a harder time finding work than the rest of the population since the pandemic. This marks a sharpreversal from long-held norms, when a newly minted college degree all but guaranteed a better shot at employment.Since 1990, the unemployment rate for recent grads almost always has been lower than for the general population.

But that changed after covid. New grads have consistently fared worse than other jobseekers since January 2021, and that gap has only widened in recent months. Thelatest unemployment rate for recent graduates, at 4.4 percent, is higher than the overall joblessness rate and nearly double the rate for all workers with a college degree, according to an analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. (Bhattarai)

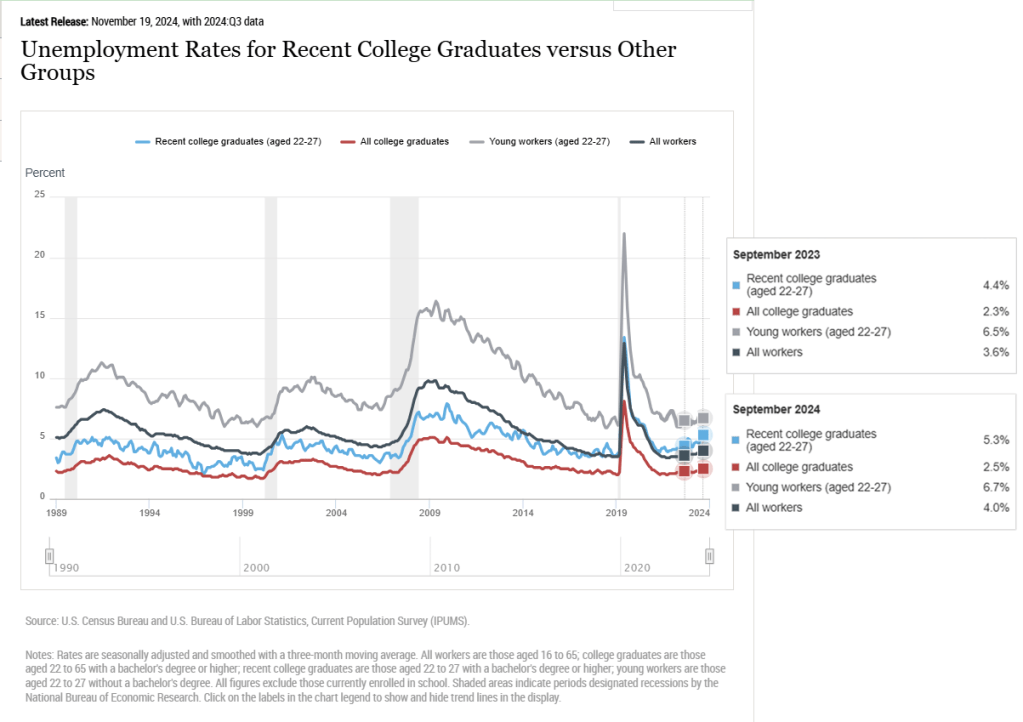

While the statistics in this article are from September 2023, they still hold true. If we look at Figure 1 below, the unemployment rate for recent graduates has risen to 5.3 percent as of September 2024 and is more than double for all workers with a college degree at 2.5 percent (“The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates”).

Figure 1

Fig 1. “The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/college-labor-market#–:explore:unemployment. Accessed 8 Feb. 2025.

Bhattarai’s article is a little misleading in that it never states the unemployment rate for all workers (3.6 percent when she wrote; 4.0 percent currently). However, it does emphasize how previous generations with a college degree were all but guaranteed to have a lower unemployment rate than the general population, but that is no longer true for recent graduates. Naturally, recent college graduates are frustrated that they are having a more difficult time finding a job than their peers who did not spend the time and money required to attend college. They feel like their investment in their future has not paid off.

Why Do the Humanities Matter?

Nowhere is this frustration more apparent than in the humanities. According to Lee Trepanier, enrollment in the humanities has dropped from 17.2 percent in 1967 to 6.5 percent in 2013 (ix). Trepanier underscores this point by explaining how the number of jobs available within these fields is significantly declining. English positions dropped by 37.7 percent, and foreign language positions decreased by 43.8 percent within six years (2007-08 and 2013-14) (Trepanier ix). Why do the humanities matter if they can’t guarantee a job after college?

While I do believe that higher education should prioritize career preparation, that’s not all it should do. The hyperfocus on career preparation is problematic in that it assumes that the only people contributing to society are those in the workforce. There are many people who contribute to society and life in deep and meaningful ways that are not strictly economic. Even for those in the workforce, their job is not the sole purpose of their life. Every single person has a life outside of work where they have friends, raise families, serve in their communities, or participate in politics. The humanities give people the skills to think critically about what it means to live a good life and how to build an ethical society.

Lee Trepanier’s book, Why the Humanities Matter Today: In Defense of Liberal Education, contains so many examples of what the humanities can offer. A different author writes each chapter about a different discipline in the humanities. For example, Kristopher G. Phillips wrote a chapter titled, “Is Philosophy Impractical? Yes and No, but That’s Precisely Why We Need It,” which argues that “philosophy can lead people to actually be more practical” (Trepanier xii). James W. Harrison wrote “The Limits of Language as a Liberal Art and Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s ‘Letter to Lord Chandos,’” which challenges how language is a framework used to make sense of the world and how language can sometimes fail to express reality (Trepanier xii–xiii). Both of these examples challenge the public’s view of the study of humanities as impractical and show its real-world applications and how society can benefit from it.

Going even further, the humanities are where social justice issues are thought about and addressed. For instance, Catherine J. Denial’s A Pedagogy of Kindness explores how classrooms can be human. One point that she makes is how “Compassion asks who is in the room, who is not, and why they are or are not there. Niceness does not” (Denial 11). If we are so focused on ourselves as individuals and how we are going to support ourselves through a job, we will never ask these questions. I would argue that the humanities ask who is in the room, who is not, and why they are or are not there. The humanities are where ethics begin.

Practical Applications

Since the humanities are essential to building an ethical society, universities should consider them a core part of their curriculum. While many universities currently have general education requirements, more weight should be given to the humanities within those requirements. Many religious universities, such as Brigham Young University, Pepperdine University, Southern Methodist University, and Texas Christian University, all have religious courses as part of their general education requirements (“BYU Catalog”; “Christianity and Culture”; “Philosophical, Religious, and Ethical Inquiry”; “TCU Core Curriculum Required Courses”). Both religious and secular universities could follow that model for their humanities requirements, where students must complete one course within the humanities each semester to build a strong ethical and civic foundation for their future selves.

Courses within the humanities could also adapt their curriculums to better address student anxieties about preparing for the workforce. For example, every student should know how to write a resume and cover letter. I believe that freshman composition is the perfect class to teach this skill of writing resumes and cover letters. One of the key learning outcomes for many freshman writing courses is to understand genre and how to write for different audiences and purposes. Analyzing resumes as a genre could be a very effective way to meet this requirement while also supporting students’ very real concerns about finding a job in the future. It could also lead to more effective applications while students are in school, such as applying for internships or summer jobs, to help make their transition from school to career smoother.

Another assignment freshman composition instructors could incorporate into their curriculum is an essay designed to help students see how writing and communication skills will apply to their future (see Appendix A). If you look at the instructions for this essay, you will see how students incorporate key terms and concepts from class and apply them to their future roles, whether that be in an academic, professional, family, or civic capacity.

By listening to student fears about future employment and addressing them in a humanities course like freshman composition, the American public can be reassured that their concerns are being heard while also preserving the humanities’ role in building critical thinking skills that are not job specific, but instead serve the social good proposed by scholars like Fitzpatrick, Denial, and Braskamp et al. The good faith that could be built from responding directly to fears about job security could help restore the American public’s faith in the humanities and help them see how the humanities can directly apply to improve their individual lives as well as improve society.

Appendix A

Future Occupations Essay*

*I did not design this assignment. I borrowed it from a WRTG 150 professor, Meridith Reed, who mentored me during my first year of teaching as a graduate student at BYU.

TASK

Our textbook, Everyone’s an Author, and your instructor have promised that what you’re learning in WRTG 150—about rhetoric, genre, information literacy, writing process, and reflection—will help you in the future. This assignment will help you see if that’s true.

Your task is to understand the communication skills that help people succeed in other college courses, jobs, family responsibilities, or community activities. You will interview someone who is further along in their academic, professional, family, or civic roles than you are now. You should choose someone you admire and someone who is doing the kind of work you imagine yourself doing someday. In the interview, you are trying to understand how this person uses rhetoric, genres, writing processes, information literacy, and reflection in their everyday lives.

You might consider asking them questions like these:

- Rhetoric and Rhetorical Situation: Who do you communicate with regularly? What are the problems you solve through communication? What are the purposes of your communication? What kind of arguments (claims+reasons+evidence) do you make? How do you appeal to your audience (ethos, pathos, logos, etc.)?

- Genre: What genres do you use when you communicate? What do those genres help you accomplish? How did you learn those genres?

- Information Literacy: What kind of information do you need? How do you find the information you need? What kinds of sources do you trust? Why do you trust them?

- Writing Process: What steps do you follow when you write? What tools are part of your writing process? Who do you collaborate with when you write?

- Reflection: Reflection means thinking about your actions and choices (cognition), evaluating your actions and choices (metacognition), and thinking about how you might act or choose in the future (action). How do you reflect on your communication? How do you reflect on your development as a writer and communicator? How do you ensure that your communication is ethical and charitable?

FORMAT

After the interview, you will write a 1000-word essay (about 4 double-spaced pages). Do not use AI for this assignment. Your essay should explain each term or concept, using what you learned from our class readings and discussions. After defining a term, you will discuss how that term applies to the interviewee’s writing context. Your essay should focus on what kind of rhetorical knowledge, genre awareness, information literacy, writing process, and reflection the person you interviewed uses as they communicate with others.

Your paper should also reflect on how your current knowledge prepares you for future communication roles and what you still need to learn about communication.

AUDIENCE

You can imagine two audiences for this assignment. The first is yourself. You should reflect on how your current knowledge prepares you for future writing. You should also reflect on the additional knowledge and skills you will need. The second audience could be other first-year composition students, and your goal is to help them understand the communication and information literacy skills they might need in the future. Because you are writing to other first-year composition students, you should use vocabulary, concepts, and terms you learned this semester as you describe and explain how people communicate.

GRADING

A – An A paper demonstrates an excellent understanding of rhetoric, genre, information literacy, writing process, and reflection. You use well-chosen evidence to show how the person you interviewed uses these concepts as they communicate with others. You identify similarities and differences between the communication concepts you learned in WRTG 150 and communicating in another context. You demonstrate exceptional ability to reflect on your current and future writing. You use language and conceptual knowledge appropriate for an audience of WRTG 150 students. Your writing is error-free and a pleasure to read.

B – A B paper demonstrates an adequate understanding of course concepts and how people use them in college courses, a career, and family and civic life. You provide adequate evidence from your interview. You use class terms and concepts. Your writing is mostly error-free, so that little static interferes with the reading.

C – A C paper demonstrates some understanding of course concepts, but you struggle to articulate and apply course concepts to the interview. Your claims may be unrelated to course concepts or unsupported by the interview. Your writing contains errors that interfere with the reading experience.

D – A D paper shows little engagement with course concepts. You don’t use course concepts to understand how someone communicates, or you don’t show that the interview was about rhetoric, genre, literacy information, etc.

Sources

“BYU Catalog.” Brigham Young University, https://catalog.byu.edu/pages/byu-catalog.coursedog.com. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

“Christianity and Culture.” Pepperdine University, https://seaver.pepperdine.edu/academics/ge/program/christianity_and_culture.htm. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

Denial, Catherine J. A Pedagogy of Kindness. University of Oklahoma Press, 2024.

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019.

Kaufman, Scott Barry. “Who Created Maslow’s Iconic Pyramid?” Scientific American, https://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/beautiful-minds/who-created-maslows-iconic-pyramid/. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

Maslow, A. H. “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, vol. 50, no. 4, July 1943, pp. 370–96. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346.

“Philosophical, Religious, and Ethical Inquiry.” Southern Methodist University, https://www.smu.edu/provost/saes/academic-support/general-education/university-curricula/common-curriculum/general-education/breadths/philosophical-religious-and-ethical-inquiry. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

“TCU Core Curriculum Required Courses.” Texas Christian University, https://provost.tcu.edu/tcu-core-curriculum-required-courses/. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

“The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/college-labor-market#–:explore:unemployment. Accessed 8 Feb. 2025.

Trepanier, Lee, editor. Why the Humanities Matter Today: In Defense of Liberal Education. Lexington Books, 2017.

Leave a comment